More than 250,000 people here in Northeast Ohio still have no power after Tuesday’s storms that toppled trees and power lines, and more than 300 utility poles. Our immediate neighborhood in Cleveland was lucky this time, but mere blocks from our home hundreds of people have no electricity.

This is a test of patience and endurance for so many people. I’m hearing from a lot of them in emails and texts, and on social media. It’s hot and humid, which compounds the suffering. I would never presume to suggest tips for coping as I sit at my desk while the air conditioner hums. A columnist should always know her audience and when to stay in her lane.

I do occasionally wander into threads complaining about the workforce tasked with repairing all the damage. I’m the daughter of a utility worker, and he has been on my mind this week. Big storms always took my father away from us, sometimes for days. I remember the look on his face whenever he finally came home, too tired to say even our names as he trudged across the living room and up the stairs to bed. Decades later, this is still the story of the men and women working right now to turn the lights back on.

My siblings and I grew up with the mascot of electricity, Reddy Kilowatt, smiling at us from potholders, jar grips and hand towels. So often, one of us kids would turn on a light and Mom would say, “Thank your daddy for that electricity.” When I was little, I used to imagine my burly father standing outside the plant on Lake Erie’s shore and hurling bolts of red lightning into our house.

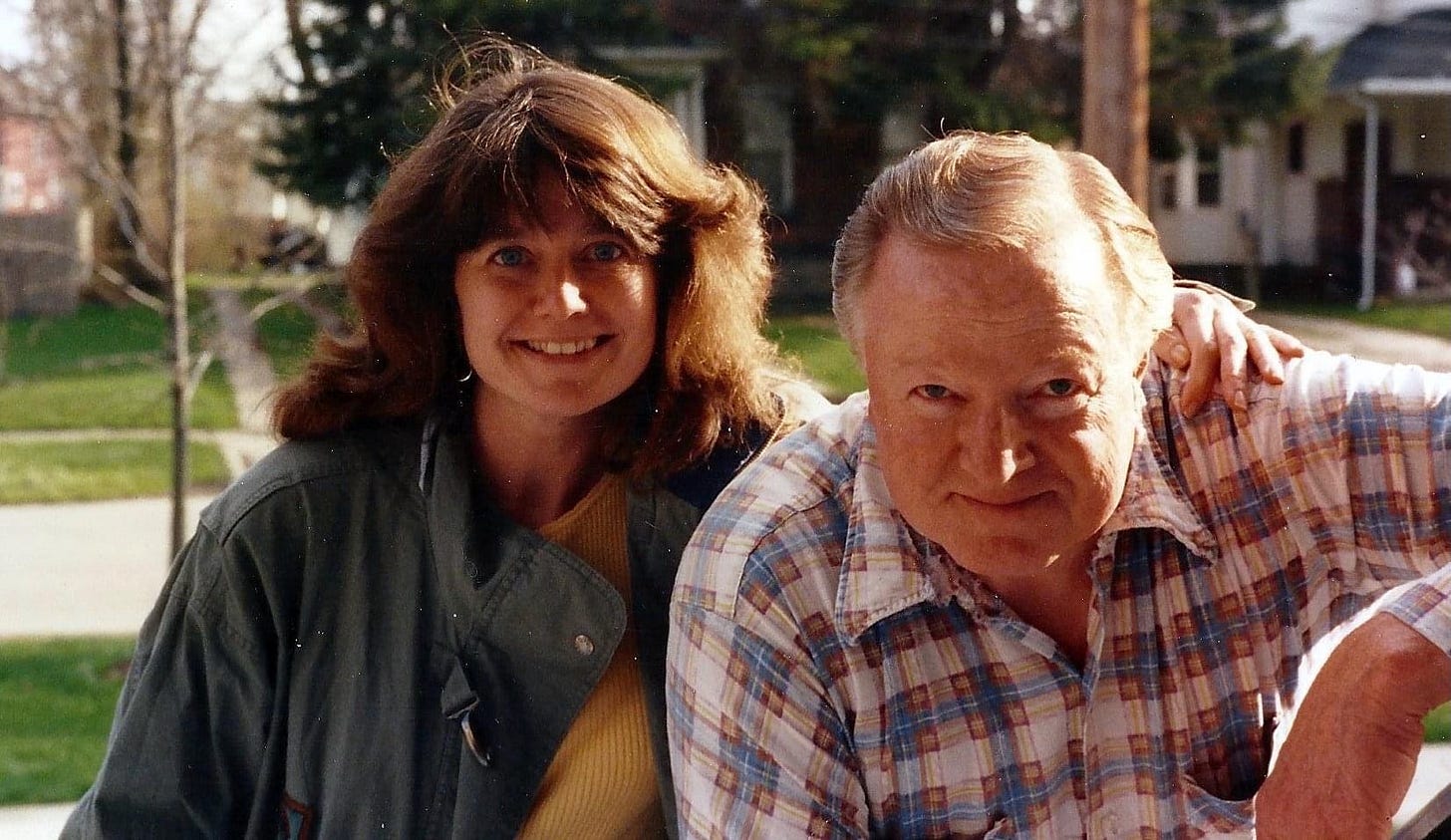

That’s my dad, Chuck Schultz, in the first photo, from the June 1979 issue of The Motor, the in-house magazine of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company. He worked for 36 years at Plant C in Ashtabula, Ohio, where I grew up. He was 42 in that photo. I was a senior in college.

I knew only two things about my father’s job: He was a proud member of Local 270 of the Utility Workers Union of America, and his job classification was maintenance mechanic.

As I wrote for Parade magazine in 2010, I saw my dad at the plant only once. I had recently gotten my driver’s license, which immediately turned me into Mom’s errand girl. On a muggy night in August, she ordered me to deliver a plate of dinner to Dad during an overtime shift. “Take Shilo with you,” she said, worried about random men approaching her daughter. (She always overestimated the protective powers of our 12-pound rescue mutt, named for the Neil Diamond song. Dust bunnies made her tremble.)

Dad always showered at the plant before coming home. He was impeccable about his appearance, and so I was used to razor pleats in his pants and the smell of Brylcreem and Old Spice when he walked through the door. I saw a different man that night.

It was dark and steaming hot, and I was annoyed to feel even more miserable standing in front of the running car waiting for Dad to show up. My grievance disintegrated at the sight of him as he walked out of the plan. He was wearing clothes I’d never seen before, and was covered in so much coal ash that Shilo didn’t recognize him and started yelping.

I stared at Dad as he reached a filthy hand through the open window and patted Shilo’s head. “It’s okay, girl,” he said, “It’s just me.” For the first time in my life, I was forced to consider why my father was so often angry for no apparent reason.

He would never talk to me about his work. “It was a job, Connie,” he’d say whenever I asked. “Not a career.” Five years after his death, his former supervisor, Toby Workman, took me on a tour of the abandoned plant and I finally learned what it meant to work in maintenance as a utility worker.

Most of Plant C was windowless and part of it was below sea level. Toby said there were days when the thermometer hit 140 degrees. We couldn’t walk five feet, it seemed, without passing another DANGER sign. Station by station, I’d ask Toby, “Did my dad do this job?”

Finally, he put his hand on my shoulder and said, "Look, you need to understand something. Your dad was a maintenance mechanic. He knew every square nook of this plant. If it was broke, he fixed it."

This was Newsweek’s cover in early December 1976, during my sophomore year at Kent State. My mother was so excited to show it to me when I came home for winter break.

“You wouldn’t believe all the calls we’re getting about this,” she said, waving it in the air. “Everybody wants to know if you’ve dropped out of school.”

She was referring to Art Seitz’s cover photo of telephone installer Joyce Kelly who, in this photo, could have been my twin. My mother thought it was a hoot that so many people thought her daughter had made the cover of Newsweek. My father had a different reaction. I was the first in our family to go to college, and he was not amused that anyone could think his daughter would squander such an opportunity to follow in his footsteps.

So many times during my childhood he would hold up his metal lunchpail and say, “You kids will never carry one of these to work.” He was working in a job that would wear his body out. He was 48 when he had heart bypass surgery. Later, he had back, hand and shoulder surgeries. When he was 69, he had the heart attack that killed him. His greatest accomplishment, he once told my mother, was that all four of his kids had college degrees.

In some ways, work conditions for utility workers have improved. In essential ways, though, the hardest parts of the job have not changed. Right now in Northeast Ohio, they are working round the clock in this miserable weather to restore power to more than 200,000 residents.

If you’re one of those residents, I hope you are finding ways to stay safe and cool. Certainly, I would never judge you for complaining. We’ve lost power numerous times in the 11 years we’ve lived in Cleveland, and self-pity finds me fast and moves in for the duration.

This is just me, acknowledging all those workers who are doing all they can to bring back the lights. This is me, a utility worker’s daughter, remembering the father who used to stand on the water’s edge and hurl bolts of lightning into the sky.

As a retired utility worker I was so proud to see my Union, IBEW 1245, endorse Harris/Walz! I hope all Union workers recognize the threat the Republican party and their Project 2025/Agenda 47 (and the tech bros backing them) pose, they are literally trying to steal your jobs. Vote 💙

I am a Clevelander who lost power Tuesday at 4pm and it just came back on today, Friday at 7am. I received a notice that I was back up. I immediately wrote back "thank you so very much". Someone wrote back your are very welcome.

Outages make you remember how much you rely on electricity every hour of the day. Bless all those hard workers.