One morning in July 2021, after spending too much time blocking yet another round of trolls on my Facebook page, I tiptoed over to Twitter to vent: “I’m thinking of writing a children’s book titled, Tom The Troll Has Been Blocked.”

I had no such plan.

I was just sick of trolls. Their profile photos on Facebook typically feature men who not so much smile as leer, and are either bare-chested or wearing military garb. They are pictured holding children or dogs, sometimes both. They show up on my page and harass dozens of women in a single discussion thread, using an identical, grammatically challenged message peppered with emojis of hearts, flowers and bolts of lightning. Because each of us is just this special, they copy and paste, copy and paste a version of the following:

Oh, your so beautiful. Your smile is a rocket flare heading into the sun. you are kind like a thousand tulips. I am lonely and rich and you with all the hair are the one I was looking for to spend all of my money. If you will just let me please, please be your Facebook friend we can begin our love affair and no pressure but you will worship me and then your heart will explode like a hurricane and I have a dog….

My response is always the same.

Block, block, blockety-block-block.

After one such block-a-thon, I announced, “Tom the troll had been blocked.” After a reader jokingly suggested that would be a great title for a children’s book, I posted that tweet on Twitter, where trolls are less enamored of women, by which I mean to say they hate us. Their attacks are personal and seldom have anything to do with the opinions we share. They despise the fact of us, and their only goal is to shame us into silence. They insult our hair, our weight, our age—anything they imagine us to be.

I wrote about some of these boys last fall, after my selfie on Election Day in Ohio triggered what is apparently a lifelong hatred for Mommy. For trolls on Twitter—and especially now on X—anyone’s mommy will do.

A few hours after my tweet about Tom the Troll, I got a call from my agent, Gail Ross, who was under the impression that I was hard at work on my next novel. I love Gail for many reasons; one of them is her gift for directness.

Our exchange:

GR: “Why the [expletive deleted] are you writing a children’s book?”

CS: “I’m not writing a children’s book.”

GR: “You are now.”

An editor named Casey McIntyre had seen my tweet, and reached out to Gail in an email:

“I run Razorbill, a children’s imprint at Penguin Random House. I follow Connie Schultz on Twitter and today she posted a cute tweet about a possible picture book about blocking trolls. I imagine she was half kidding, but I think it’s a really interesting idea and I’d love to talk more with her agent about it….”

Holy cannoli.

I revere good picture books for children, so much so that I never dared think I could write one. Long after my two children were grown, I continued to collect them--books, not children, unless we’re talking about grandchildren. We have eight of those, and now an entire bookcase in our home is full of stories that ignite the imaginations of children and animate the grown-ups who read them aloud.

For the first time in my career, an editor wanted me to write a children’s book. Talk to this Casey McIntyre, I said to myself. Thank her for reaching out and explain why you are not qualified to do this.

Six days after that tweet, I signed into a Zoom meeting with Casey. By the end of our hourlong conversation, she could have told me I can fly with my own wings and land in high heels, and I would have jumped out the nearest window to prove her right.

When I told Casey I’d never written a children’s book, she laughed and said it was time that I did. When I said I was nervous, she assured me she’d be with me every step of the way. When I admitted to being excited, she laughed again and said, “Good, because I’m crazy excited for this book!”

She was nearly half my age, constantly smiling and blunt, in the best of ways. She told me she was a survivor of ovarian cancer, and quickly moved on. She talked about her husband, Andrew Rose Gregory, in glowing terms and then asked if my husband was as nice as he seemed in my photos. When I laughed, she admitted she regularly looked at my Instagram, where we already followed each other.

“Look,” she said. “I’ve seen those pictures of you with your grandchildren. I know how much you love children, and I know how you write. You’re ready for this, and so am I.”

Her faith in me became my promise to her: I would write a children’s book about a troll and a brave little girl who learns to stand up to him.

Casey helped me keep that promise. She was one of the best editors I’ve ever worked for in my 40 years as a writer. True to her word, she helped me every step of the way. Often, that help came in the form of a well-timed nudge.

It was important, she said, to visualize my characters long before we entrusted them to an illustrator. Her prompt: “Imagine that little girl to be someone you know.”

Almost immediately, that child became Lola, who looks a lot like our granddaughter Ela, who was four at the time. A few days later, Casey laughed when I told her our scraggly little rescue dog, Walter, would be the perfect model for Lola’s steadfast and invisible companion, Tank. (He’s small on the outside, big on the inside.) Ms. Sneesby, Lola’s good friend who owns the local bookstore, looked a bit like a former hippie.

I couldn’t picture the troll, and Casey recommended we leave that to the imagination and talents of Sandy Rodriguez, the illustrator we had agreed was the best person to bring all the characters to life. Boy, were we right to trust her.

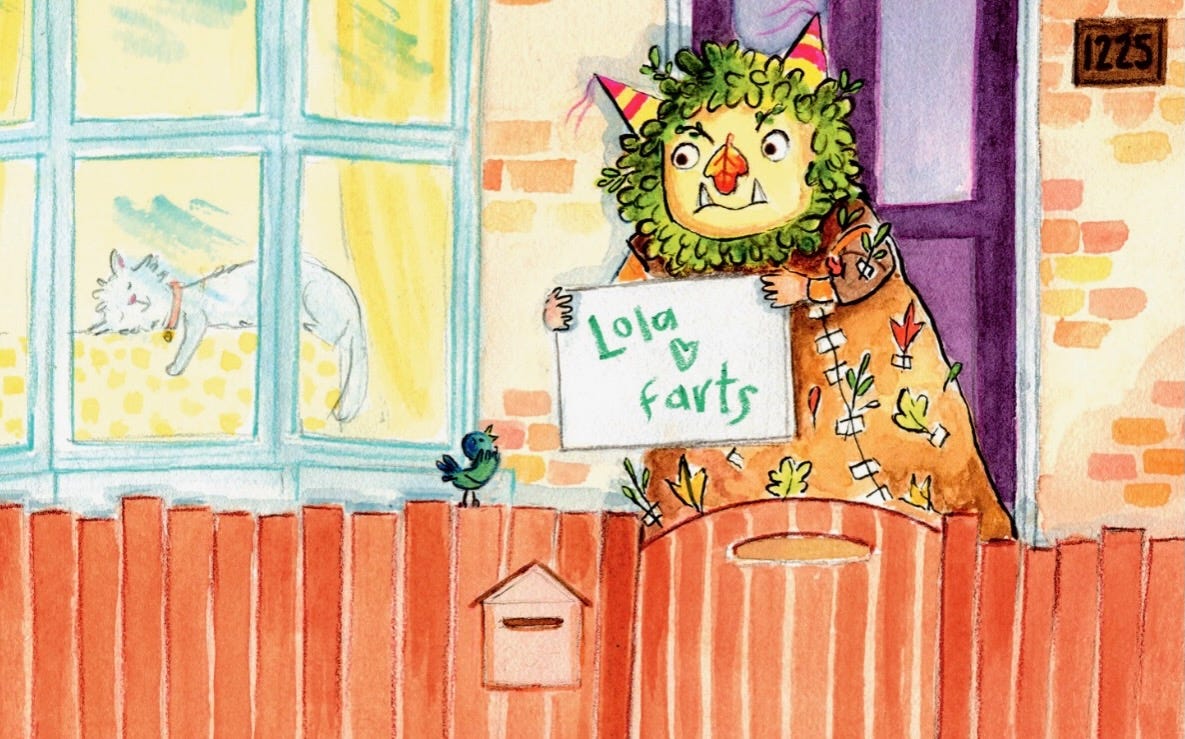

It took a while for me to figure out how Tom the Troll would bully Lola in a way that resembled trolls on social media. Finally, through brainstorming with Casey, he became that guy who scrawls insults on signs that he holds up as Lola walks past his house. By then, I knew Casey’s method of approval: I told her my idea and she laughed, hard. A week later, I told her how, with each sign the troll held up, Lola was trying to change another part of herself. “That guy,” Casey said, growling into the phone.

Casey knew how to edit in a way that let me be in control of my story. Almost always, her suggestions made it better. At one point, Tom the Troll tells Lola her voice is too loud, and so she begins to whisper everywhere she goes. Her parents lean in, trying to hear her.

Casey suggested that Tank, who is always at Lola’s side, hold up an ear trumpet as she talked. Every time I see this illustration by Sandy, I think of Casey laughing as she said, “That Tank. So much drama.”

Lola and the Troll comes out on February 6, and publicity is gearing up. Like many writers, I’m uncomfortable with the self-promotion aspect of publishing, but I’m trying to do my part to let the world know about this dream come true. I want to introduce children to brave little Lola, but that’s only part of the reason I’m telling you about my book.

I wanted you to know Casey.

A few days ago, a box from Penguin Random House landed on my porch. A big day for an author, when you can finally hold the book you’ve been working on for years. I was overjoyed at the sight of Lola and Tank on the cover. Moments later, I was sitting with my head in my hands, overwhelmed with the grief I’ve been trying to keep tucked away.

The person I had most wanted to call was Casey. I will never hear her voice again.

On November 13, 2023, Casey’s final Instagram post appeared. It was a written message under a series of photos of her and Andrew, and their young daughter, Grace:

A note to my friends: if you’re reading this it means I have passed away. I’m so sorry, it’s horseshit and we both know it. The cause was a recurrence of my previously diagnosed stage four cancer.

I loved each and every one of you with my whole heart and I promise you, I knew how deeply I was loved.

The five months in home hospice that I got to spend with my family and friends in Virginia, Rhode Island and New York were magical.

She was 38.

Andrew added an “editor’s note” to her post, which included Casey’s hope for a celebration of her life that would include a fundraising effort to purchase the medical debt of strangers who can’t afford to pay it. Word got out quickly, igniting a lot of news coverage.

Through the website RIP Medical Debt, Casey’s Memorial & Debt Jubilee has raised more than $1,084,200. As NPR reported, “the group says that for every dollar it receives in donations, it can relieve about $100 of medical debt.” By November 27, 2023, the day of that story, donors had already helped Casey raise more than $70 million in canceled medical debt.

I had known she was sick, but I did not see this coming.

Soon after Casey had approved the final version of my story, she went on maternity leave. Her messages were full of excitement as she and Andrew prepared to welcome their baby, who would be born via surrogacy. What I didn’t know is that two weeks after Casey and Andrew knew they were having a baby, she found out her cancer had returned.

She never told me. For as long as she could, she sent encouraging notes about Lola and an occasional photo of baby Grace. Eventually, Casey went on medical leave and her notes stopped. Through her Instagram photos, I could see that she was growing thinner and her hair was short again. It was clear she was cramming in as much time as possible with Andrew and Grace, and other people she loved.

She had given me her personal email address, and I sent an occasional note of encouragement. In my final email, last June, I told her I missed her but that nothing mattered more than her recovery.

“Lola exists because of you,” I wrote. “You tossed me the key and I unlocked the door to a new adventure I had never dared to believe existed for this writer. I am forever grateful to you. I hope one day to greet you in person. You’ll need to brace for that hug….”

Simone Roberts-Payne is now my editor. She is smart and kind, and every time I see her name pop up in my inbox, I think of how gracious she has been in this time of grief for everyone who knew Casey. The entire PRH team has helped me feel excited about my book. Casey would have loved that about them. I surely do.

For weeks, I have struggled with how to write this essay. I’ve wanted to let you know about my book, and I could not do that without also telling you about Casey. Last Wednesday evening, I held my book for the first time. There was Lola, looking at me with her hands on her hips. Waiting.

It was the nudge I needed.

I’ve worked for a lot of editors in my career. Some I love, some I could have done without. Casey is in a category by herself. Not because of how she died, but how she lived. In the days after her death, Andrew shared on social media many photos of Casey, and the tales behind them. They told the story of a woman who ran into life with arms wide open. No wonder she became an editor of children’s books. She believed in the magic.

I’m not sure what she would have made of this essay, but she knew my plan. She was part of Lola’s story, and she knew I planned to let readers know all about my editor. “They will know your name!” I often told her, loudly. She always laughed.

This is me calling, Casey. Promise kept.

Wow. That essay---cracked my ancient heart in two. I am so so so sorry for your loss and the world’s loss. And I am buying your book for all my grandchildren--boys and the lone little girl. You are a light in a darkening world. I think (just made the mistake of reading the Sunday newspaper) --full of despair about our sad world--your light and kindness and Casey’s remind me that darkness wins when we, out of fear, extinguish our own light. So shine on my friend! Shine on!

It’s so *Connie* to make sure everyone is celebrated for their contributions.

Thank you.

And now, I need to go donate to RIP Medical Debt.